- Home

- Stephen Klaidman

Sydney and Violet Page 2

Sydney and Violet Read online

Page 2

Whatever Alfred’s intentions and expectations might have been, Sydney’s first several months on the ranch appear to have been happy. He enjoyed caring for the horses, he didn’t complain about loneliness or lack of comfort, and the owners, his father’s friends Sir John Lister-Kaye and his wife, Natica Yxnaga del Valle, made him feel at home. But some months later the Lister-Kayes were suddenly called back to England and left Sydney in charge of the ranch, a responsibility the nineteen-year-old was not eager to accept. Moreover, by then he had been there for almost a year and was getting restless. In any event, he packed up and headed for Cincinnati, three thousand miles to the southeast, to visit his father’s brother Charles, a railroad executive there.

Sydney’s most detailed and extensive account of his sojourn in Cincinnati occurs in The Other Side, the last book he wrote, which appears in its entirety in his multivolume autobiographical novel A True Story. In it he offers a fictionalized account of the logistics surrounding the last great bare-knuckle boxing match in America, between John L. Sullivan and Jake Kilrain. Charles Schiff almost certainly authorized one of his railroads to provide transportation to the fight’s site in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, but Sydney’s suggestion that he played a role in getting his uncle to comply is fiction. The date of the fight is not consistent with his time in Cincinnati.

Charles Schiff and his Nashville-born wife, Mamie, welcomed Sydney warmly and like the Lister-Kayes made him feel at home, but he interpreted certain elliptical remarks by his uncle to mean that his stay was intended to be long and possibly open-ended, a prospect he found disconcerting. He concluded his father had conspired to get rid of him and his uncle was complicit. For a while he was given the freedom to explore his new surroundings. Eventually, though, Charles Schiff received a letter from his brother that prompted him to put Sydney to work. He gave his nephew a few more days to settle in and then told him there was a job waiting for him in the railway’s head office. When Sydney found out what was in store for him, he considered leaving Cincinnati and traveling. But he soon realized he had no idea where he would go, so he accepted the job. The next day he began training as a clerk in his uncle’s office. The work, checking other people’s addition, was mind numbing. He only had to do it for a week, but the immediate future didn’t seem any brighter.

Soon thereafter Sydney told his uncle he didn’t think he was cut out to work in a railroad office. Charles Schiff, carrying no paternal baggage, was much more sympathetic to his young nephew than his brother Alfred would have been. He took his nephew’s resignation in stride. He also concluded that Sydney would not benefit from spending more time in Cincinnati. While not exactly throwing him out, he advised him to see more of the United States, a suggestion Sydney by then was ready to accept.

A MISERABLE MARRIAGE

Sydney made his way to Louisville, Kentucky, little more than a hundred miles southwest of Cincinnati, but culturally much more southern. He must have had at least one introduction to someone there because he almost immediately met Marion Fulton Canine, whom many years later he would portray as Elinor Colhouse in A True Story. She was the dark-haired, olive-skinned eighteen-year-old daughter of a once-prominent dentist named James Fulton Canine whose taste for alcohol had decimated his practice. Sydney was instantly smitten by her beauty—by some accounts, she was the belle of Louisville. Less obvious to Sydney, who was twenty and not especially sophisticated, was that she was willful and single-minded. She was dead set on finding a husband who would dramatically improve her social and economic prospects. Here’s how Sydney described Elinor’s initial reaction to Richard Kurt in the novel Elinor Colhouse:

“Her first impression of Richard as he rose from an arm-chair beside the fireplace to meet her was that he was tall and slim and looked like a boy. The shutters were partly closed, but she could see that his hair was light, his eyes were dark and that he had a fair mustache. His accent, she thought approvingly, was very English.” In contrast to Sydney’s shy demeanor and lack of experience, Marion was womanly, self-assured, and socially adept. His immature appearance and social awkwardness, if he had been an otherwise eligible suitor from Louisville’s professional class, would have guaranteed that his first meeting with Marion would have been his last. But Marion, perhaps because of her family’s straitened circumstances, had perfected her own fiscally sound standard for calculating a young man’s eligibility. It was instantly apparent to her that Sydney had advantages to offer that the young men of her Louisville circle could not hope to match. He was an English gentleman, which to her way of thinking placed him cuts above the best local society. But more significantly, there was this elegantly simple fact: his family was rich on a scale unattainable, at least by her, in Louisville. She told her mother bluntly that Sydney met her well-defined requirements for a husband, no one else did, and she was not going to let him get away.

Within a couple of months of the day they met, Sydney and Marion eloped. They were wed in St. Luke’s Church, Sault Sainte Marie, Ontario, Canada, on August 29, 1889. Both Sydney and Marion lied about their ages, he claiming to be twenty-five (he was four months shy of twenty-one) and she twenty-one. Sydney listed his profession as gentleman, his residence as London, England, and his parents as Alfred G. and Carrie Schiff. Marion gave her full name as Marion Fulton Canine and those of her parents as James F. Canine and Elizabeth Canine.

Sydney and Marion returned to Louisville a married couple, but considering that Marion had not asked their permission to wed and had denied them the pleasure of seeing her as a bride the reception they received from her parents was not necessarily warm. On the other hand, given the economically parlous condition of the Canines, an alliance with a wealthy English family might have mitigated their disappointment.

The young couple stayed only briefly in Louisville and what happened next is somewhat murky. Sydney and Marion might have traveled to Cincinnati to introduce Marion to Charles Schiff and his wife because Sydney wanted his uncle to break the news to his parents, whom he still hadn’t told he had a wife. The Cincinnati Commercial Tribune reported the marriage on September 12 under the headline: “Marriage of a Well Known Young Railroader to a Louisville Lady.”

Sydney knew his father would be apoplectic when he found out his son had married without his consent and was even afraid Alfred might disinherit him. He also knew his new wife’s unimpressive social status—American of no particular background and very modest means—would make matters worse. But his greater concern was for his mother, the former Caroline Mary Ann Eliza Scates, with whom his relationship was as warm and close as the one with his father was cool and distant. She had been diagnosed with valvular heart disease, a condition for which at the time there was no treatment, and he worried the news might come as a devastating shock to her.

Even Alfred, who continued to have serial affairs despite his wife’s illness, was concerned enough to buy a villa in the south of France to get her away from the bustle of London. He chose a house in Roquebrune, a historic town set on a tranquil hillside that was for centuries the property of the royal family of Monaco. It is hard to say whether the quiet life was good for Caroline’s health, but the proximity to Monte Carlo was disastrous for Alfred’s gambling habit. He made multiple daily trips to the casino during their eight-month annual stays and ultimately squandered half his fortune at the gaming tables, which, it is not hard to imagine, must have been distressing for her.

Sydney’s concern that his parents would be incensed by his marriage was not unfounded. Alfred and Carrie, as all who knew her called Caroline, were extremely upset when they found out about the marriage. But between the time they learned of the wedding and Sydney and Marion’s arrival in London, they managed to repress their anger and disappointment. They welcomed the young couple with well-bred civility, if not familial warmth. Sydney and Marion settled into a small but comfortable flat found and paid for by Alfred, who also gave Sydney a small allowance and a job at the bank. Sydney, for his part, for once did what was expected o

f him. He accepted the job. What he fervently hoped, however, was that his tenure would be short and at the end of it he would get enough money from his father to pursue his still-developing interests in art, literature, and high culture generally, without having to earn a living.

While he was not exactly happy with the arrangement, Sydney resigned himself to it. Marion, however, would have none of it. She had arrived in London with grandiose expectations unrelated to culture or, it seems, reality, and demanded instant gratification. She began whining almost immediately about their small, unfashionable flat, her husband’s meager income, and the failure of the senior Schiffs to bestow on her the diamonds and furs she believed were the perquisites of her recently acquired status. What’s more, she drove Sydney’s mother to distraction by “making all kinds of [unspecified] mischief involving friends and family,” all the while seeming oblivious to the self-destructive effect her behavior was having.

Although she probably could have gotten away with complaining to her husband about how deprived she felt, her frequent shrill bitching to his parents quickly wore out their grudging welcome. The only thing that kept Alfred from withdrawing all support from Marion—and Sydney—was his concern about aggravating Carrie. But before long Marion’s provocations became intolerable and he decided to put an end to them. He probably would have liked to cut off the two of them completely and send them away empty-handed, but Sydney was Carrie’s favorite child and a gentler solution had to be found. His pragmatic accommodation was to give Sydney enough money to take Marion away from London and keep her away for as long as necessary.

Sydney, while troubled by his mother’s illness, was pleased with his father’s decision. He was eager to travel with the leisure and comfort Alfred’s money would afford. One might easily imagine, though, especially at that particular moment, that Marion was hardly his ideal traveling companion, if only because of the insufferable way she had treated his mother. But it went deeper than that. He makes clear in A True Story that his doubts about committing to a life with her began as soon as he proposed. It even appears likely he shared them with her almost immediately afterward. But having bagged her quarry she was not about to lose it. And despite his strong doubts, once having made a commitment his own youthful sense of honor would have prevented him from breaking it even if he sensed a disaster in the making.

So Sydney, cash and credit in hand, fluent in French and German and eager to explore European art and architecture, and Marion, financially and linguistically dependent and with little awareness of or interest in anything European but Paris and the Swiss Alps, set off for the Continent. What pleasures, if any, they shared during their wanderings, which consisted mostly of flitting from chic spa to elegant resort to cultural icon, are unknown. But somehow they managed to do it for more than five years, leaving no trace of their travels and returning to London only when Carrie died in 1896 at fifty-two. They stayed just as long as was absolutely necessary, which probably was not their choice, but Alfred’s.

As soon as seemed decent after Carrie’s death Alfred Schiff settled a sum of money on his wayward son sufficient to provide a gentleman’s income for the rest of his life, but less than his full inheritance. He then bought a large villa on Lake Como for the couple not to own but to occupy and gave them money to furnish and refurbish it, which they did. They then lived in it—unhappily—side by side, but not together, for the next thirteen years.

In Elinor Colhouse, the second volume of A True Story, Sydney provides a kind of psychobiographical account of his dismal life on the lake in which he meticulously records his feelings but takes liberties with everything else. For several months he and Marion worked to restore the lakeside villa to its former gracious state, a project that united them for once in pursuit of a common goal. They were obsessed, possibly for the only time in their lives, with the same thing, which led to something resembling intimacy, a condition previously unknown to them. As they worked together toward a common goal they experienced mutual satisfaction, probably for the first time in their lives. They didn’t even clash over matters of taste. They reveled in the villa’s slick marble walls, the green and gold brocade chairs they fastidiously set against them, the laurel scrolls, garlands of flowers, and quivers of arrows, all in stucco, the Louis Quinze gilt brackets, and more, much more, all illuminated by a stunning array of electric lights. Was it over the top? For today, probably, but for their class in that time and place perhaps not.

Predictably, when the work on the villa inside and out neared completion, so did the tenuous period of comity between Sydney and Marion. She soon resumed regular outings with her entourage of admirers and reverted to the testiness and disdain that had long characterized her behavior toward him. But this time Sydney was less vulnerable, even indifferent to her torments. This was because nearing forty he had found a source of consolation of his own, a woman he called Virginia Peraldi, whose family and Sydney’s actually were acquainted. She was a strange girl, half English, half Italian, seventeen or eighteen years younger than himself and a religious Catholic. In A True Story Sydney wrote that this relationship ended unsatisfactorily during a trip they took together to Milan to meet his father, who was sick and would soon die. The news of his father’s illness stirred up a brew of conflicting feelings in Sydney, but most of all he wanted to tell Alfred that he had come to realize his own shortcomings and understood that his father’s judgment of him had been more just than he had realized. Soon after his father died in 1908 he worked up the courage to leave Como forever, but not to divorce Marion.

A NIGHT AT THE OPERA

In the spring of 1909, Sydney arrived in London after several months of traveling in Europe. The city had been transformed during his generation of wandering in North America and Europe. With Queen Victoria’s death on January 22, 1901, in the sixty-fourth year of her reign, a new century and a new age had begun. Gaslights had been replaced by electric lights and horse-drawn vehicles were rapidly giving way to automobiles and motor buses. In 1887, the year Sydney left for Canada, central London’s streets—although not those in the Schiffs’ neighborhood—were choked with coal wagons, carriages, and carts of all kinds. Cattle, sheep, and pigs were driven through those same streets to markets at Islington and Smithfield, as a result of which millions of tons of manure were dropped annually. The stench was poisonous, perpetual and omnipresent. And then there was the noise, a rumbling, inescapable din from the trampling and rattling of horses, cattle, and carts on the cobblestones. By 1909, though, the city had become cleaner and quieter. Theaters were showing silent films, the Victoria and Albert Museum had been completed, and so had Westminster Cathedral and the Imperial Institute.

The passing of the crown to Edward VII marked an intellectually disconcerting transition from Victorian customs, practices, and mores, both overt and covert, to an evolving Edwardian ethos. A new temperament, for better and worse, was being fashioned, partly by the advent of automobiles and assembly lines, telephones and moving pictures, Marxism and feminism, relativity and quantum physics, and, of course, psychoanalysis. Mechanization, innovative uses of electricity and other scientific and engineering advances were rapidly replacing Victorian-era transportation, communications and manufacturing techniques, while radical social ideas were challenging class and role rigidity and reshaping how people thought about the universe and their place in it. At the same time, new values and ideas were also transforming literature, music, and the plastic arts in ways that would come to be known collectively as modernism and would radiate around the world, changing the cultural environment of cities as distant from one another and as disparate as New York and Shanghai.

London was meant only as a way stop for Sydney on a trip designed to clear his head and help him figure out how to end his dolorous marriage—with propriety and honor—and begin a new life. As a result, he would not have expected to stay long or to be much affected by these social and cultural changes. But about both of these things he would be wrong. Modernism and its value

s would alter his future in ways he could not possibly foresee. But that time was still to come. For the moment he was profoundly unhappy not only with Marion, but because by his own sad reckoning he had lived forty years and accomplished nothing. He was desperate to find an escape route.

Part of his problem in ending his marriage was that the chivalry he portrayed in Richard Kurt, his fictional self, which he displayed as a mere boy and that seemed so naive at the time, turned out to be bred into Sydney Schiff. Despite all the pain Marion had caused him, and the changing mores of the times, he seemed incapable of branding her with the stigma his Victorian upbringing had taught him was the fate of divorced women. There can be no doubt that he desperately wanted to be rid of her. She had treated him almost from the outset with indifference, mockery—especially of his nascent literary efforts—and contempt. She was unavailable to him physically, emotionally, and intellectually. But by his rigorous standards of decency, and perhaps his concern for how polite society would judge him, none of this was enough to release him from his perceived obligation to protect her from any social retribution that might result from a divorce. He had been struggling with this conundrum for years and was no nearer a solution when he arrived in London except for one thing. He was in possession of his full inheritance and therefore could make Marion financially secure.

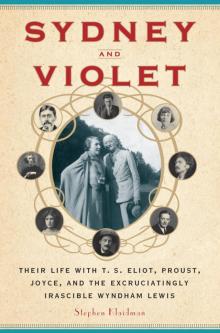

Sydney and Violet

Sydney and Violet