- Home

- Stephen Klaidman

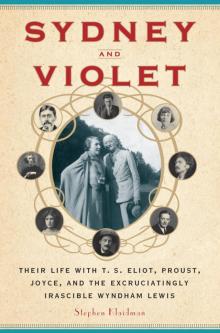

Sydney and Violet

Sydney and Violet Read online

Copyright © 2013 by Stephen Klaidman

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, a division of Random House, LLC., New York, a Penguin Random House Company, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Toronto.

www.nanatalese.com

DOUBLEDAY is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House, LLC.

This page–this page constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Jacket photographs: T. S. Eliot and Aldous Huxley © Everett Collection Inc./Alamy; Ezra Pound © Pictorial Press Ltd./Alamy; James Joyce, Marcel Proust, and Dame Edith Sitwell © Hulton Archive/Getty Images; Katherine Mansfield © Keystone-France/Getty Images; Lady Ottoline Morrell © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Jacket designed by Emily Mahon

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Klaidman, Stephen.

Sydney and Violet : their life with T. S. Eliot, Proust, Joyce, and the excruciatingly irascible Wyndham Lewis / Stephen Klaidman. — First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Hudson, Stephen, 1868–1944—Friends and associates.

2. Modernism (Literature). I. Title.

PR6037.C37Z73 2013

823′.912—dc23 2013006199

eISBN: 978-0-385-53410-9

v3.1

This book is for Kitty, my love, my joy, my inspiration.

May truth, unpolluted by prejudice, vanity or selfishness, be granted daily more and more as the due of inheritance, and only valuable conquest for us all!

—Margaret Fuller, from the preface to Woman in the Nineteenth Century, November 1844

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

A NOTE TO READERS

PROLOGUE

Chapter 1 SYDNEY’S TRAVELS

Chapter 2 FAMILIES

Chapter 3 THE MODERNIST WORLD

Chapter 4 THE WAR YEARS

Chapter 5 A VOLATILE RELATIONSHIP

Chapter 6 ANNUS MIRABILIS

Chapter 7 A FRIENDSHIP IN LETTERS I

Chapter 8 A FRIENDSHIP IN LETTERS II

Chapter 9 A FALLING-OUT

Chapter 10 NEW FRIENDS

Chapter 11 THE APES OF GOD AND MODERNIST SATIRE

Chapter 12 VIOLET ALONE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

PERMISSIONS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Illustration Credits

Other Books by This Author

A Note About the Author

Illustration Insert

A NOTE TO READERS

In an age of literary license in which memoirs and autobiographies are often imaginatively embroidered, I prefer to begin with full disclosure. This book portrays the title characters and the glittery modernist milieu they inhabited. But there are many gaps in the record of Sydney’s and Violet’s lives, especially before they met. A thorough account would have been futile without conjecture. Documentation of their life together is better because they and their contemporaries were avid correspondents. More than twelve hundred letters survive, which is why we know as much as we do about them. Regrettably, though, most were written to them, not by them. Of the ones they did write, Violet’s were in an often unreadable, self-acknowledged chicken scrawl, and not one was from Sydney to Violet or from Violet to Sydney. The cause, as in the similar cases of Joan Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, and Joyce Carol Oates and her husband, Raymond Smith, was that they were almost never apart. Sydney wrote to his friend Max Beerbohm that “except for two or three times we’ve not been separated for more than a few hours.” Evocative scraps of information from family members and friends remain along with marriage and divorce records, birth and death certificates, and a will. But beyond these meager remnants the biographical background would fade to black if not for one crucial exception: Their lives were tightly entwined with many of the defining figures of literary modernism. Because of close relationships and extensive correspondence with Marcel Proust, T. S. Eliot, Wyndham Lewis, Aldous Huxley, and Katherine Mansfield, among others, far more is known about them than would otherwise be the case.

The biggest challenge in writing this book was deciding how to overcome the lack of information about Sydney’s life before he married Violet. Apart from the sketchy documentation noted above, the only significant source material is the provocatively titled A True Story, a sprawling fictionalized autobiography influenced by Proust, written by Sydney using the pseudonym Stephen Hudson, and edited, perhaps heavily, by Violet, in which Sydney is portrayed as a character called Richard Kurt. It is tantalizing because it is rich in insight, feeling, and detail, but frustrating because there is no way to verify much of it. The Schiffs’ nephew, Edward Beddington-Behrens, wrote in his own autobiography that with the exception of what he called “external details” everything was true. But there is no way of knowing exactly what he thought was true.

Faced with these uncertainties, I have drawn on A True Story in recounting Sydney’s life before Violet and aspects of their life together. The novel offers insights into what Sydney thought about himself, or perhaps what he would have liked to think about himself. There are lacunae in Violet’s early personal and family history as well, but her background is better documented than Sydney’s. She had distinguished ancestors whose lives have been recorded, family memoirs survive, and there are several living descendants who have preserved fragments of oral history, papers, and photographs.

Caveat lector.

—SDK

PROLOGUE

London, where Sydney and Violet Schiff were born and where they were based between 1911, the year they were wed, and 1944, the year Sydney died, was the undisputed capital of the English-language literary world. It was also the baptismal font of modernism. There were important outposts, most notably in Paris, but also in Rome, Berlin, New York, and even Chicago. But the seminal modernist creed was composed in and disseminated from London. The most influential “little magazines” were published in London and the poets and novelists with whom modernism is most closely identified lived and worked either there or in Paris. These were Sydney and Violet’s colleagues and friends. They included T. S. Eliot and Marcel Proust, Aldous Huxley and Katherine Mansfield, and the now mostly forgotten writer, painter, polymath, and insufferable curmudgeon Percy Wyndham Lewis. Eliot, Mansfield, and Lewis read, reviewed, praised, and criticized Sydney’s novels and published his stories and translations in their journals. And Sydney and Violet reciprocated, critiquing and publishing their articles, stories, and poems and soliciting contributions from Proust for Eliot’s Criterion.

The Schiffs were accomplished hosts, and invitations to their homes in the city and country were avidly sought. Evenings consisted of small dinners with sparkling conversation and vintage champagne followed by wicked games usually involving role playing. They were respectful of their guests without being deferential, intellectually curious without being intellectually arrogant, and physically attractive. Violet, whose Semitic background was evident, was in her mid-thirties when they were married. She wore her dark hair piled atop her head in the style of the time, her eyes were brown with long lashes, and she had the slim, graceful fingers of a musician. Her gaze was unself-conscious, reflecting her confidence and interest in others. Sydney, who was in his mid-forties, wore a sandy-colored toothbrush mustache and carried himself with what looked to some like military bearing and to others like pretentious posturing. In either case the image was undercut by his sad brown eyes, a side effect of twenty years of heartache produced by his first wife’s r

elentlessly demeaning treatment.

Although the modernist world Sydney and Violet inhabited was internally disorganized, modernism had no organized competition. If you were a writer, painter, or composer during those years there was no escaping its influence. None of this, however, presupposed tranquil acceptance of a single view of modernism. To the contrary, divisions about the meaning of modernism, both as an aesthetic idea and as a way of life, although sometimes intellectually trivial, were often socially divisive. As a result, factions were formed, fences were built, and vituperation emerged as the extreme sport of the day. The two principal factions were deliciously contrasted by the acid-tongued poet Edith Sitwell.

“On the one side,” she wrote, “was the bottle-wielding school of thought to which I could not, owing to my sex, upbringing, tastes, and lack of muscle, belong.” With this taut description, as with a wave of the hand, she dismissed Ezra Pound, Eliot, Lewis, and their cohorts, most of whom lived in the London district known as Bayswater. She saved her undiluted invective, however, for the relatively effete intellectual alternative whose members resided in the neighborhood known as Bloomsbury. The “society of Bloomsbury,” according to Sitwell, was “the home of an echoing silence.” She said it was described by Gertrude Stein as “ ‘the Young Men’s Christian Association—with Christ left out, of course.’ Some of the more silent intellectuals, crouching under the umbrella-like deceptive weight of their foreheads, lived their toadstool lives sheltered by these. The appearance of others raised the conjecture that they were trying to be fetuses.”

A less colorful but more devastating critique of the moral world inhabited by the Woolfs, the Bells, and their circle came from one of their own, John Maynard Keynes. The Bloomsburys’ ostensible ethical touchstone was G. E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, a moral treatise whose pleasure-laden values of love, aesthetic experience, and the pursuit of knowledge they subscribed to religiously while regularly ignoring its guiding principle of benevolence. Many years after the heyday of Bloomsbury, in an essay called My Early Beliefs, Keynes wrote, “We were … in the strict sense of the term immoralists.… we recognized no moral obligation on us, no inner sanction to conform or obey.” Citing this confession, if that’s what it was, by a leading Bloomsbury figure is not, however, meant to suggest that Bayswater was morally superior—different, perhaps, but not holier.

The Schiffs, who were not especially ideological, were attracted to the conservative Bayswater element among the modernists more likely because of their aesthetic rather than their social or political preferences. They had almost no contact with the Stephen sisters, better known as Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell, or their husbands, Leonard and Clive, respectively, or with the art critic Roger Fry or Keynes. To be fair, there is no evidence they were eager to socialize with them. In one rare instance the Schiffs did attend a tea at Clive and Vanessa Bell’s, which prompted Violet to write archly to Wyndham Lewis—who had his own self-interested flirtation with the Woolfs and their crowd—“We have just penetrated to the heart of Bloomsbury.” It was, as things turned out, a rare if not singular penetration.

But there is a view of Sydney and Violet—Sydney especially—that was too widely held at the time to be ignored and that if correct, which I don’t think it was, would suggest they did want to be admitted into Bloomsbury society. It is that they were irrepressible social climbers and could not possibly have resisted courting that intellectually prominent congregation. But even if they had sought entreé, their close association with Bayswater probably would have kept them out. Although they occasionally met, and sometimes showed respect for each other’s work, by and large Bloomsbury and Bayswater lived in mutual contempt. In the Schiffs’ case, Bloomsbury’s bountiful snobbery, intellectual and otherwise, might also have played a role. Who were these Schiffs, after all? What had they done? Weren’t they just a couple of rich poseurs, pseudo-intellectuals, sycophants? Only Eliot, whose ability to suck up rivaled his (not unjustified) lofty opinion of his intellectual stature, moved easily between the two factions.

Another world from which Sydney and Violet were excluded, or at least which they never entered, was known as Garsington. Although many who were or would become their friends, such as Huxley and the painter Mark Gertler, were habitués. Eliot and his wife, Vivienne, were frequent guests, and even Lewis turned up occasionally, but there is no record of Sydney and Violet ever having been invited. Garsington was the name of the country house of Lady Ottoline Morrell, the horse-faced yet oddly attractive keeper of a hedonistic salon for, among others, sophisticated pacifists of the Bloomsbury persuasion who wished to rusticate in luxury in the years leading up to and during World War I. Despite her hospitality, she was devilishly satirized in many novels written by her guests, including ones by D. H. Lawrence (Hermione Roddice in Women in Love) and Huxley (Priscilla Wimbush in Crome Yellow), and in a novella by Walter Turner (Lady Caraway in The Aesthetes). Osbert Sitwell also caricatured her as Lady Septugesima Goodley in a story called Triple Fugue. His description of her seemingly endless nose, isosceles chin, shocking red hair, and extraordinary height was glaringly obvious.

This kind of satire of persons who were meant to be your friends and were often your hosts and benefactors, and which might more precisely be called character assassination, was endemic among the modernists. In due time, Sydney and Violet would become the victims of a lengthy, unusually mean-spirited caricature in this vein created by their frequent guest and beneficiary of their patronage, Wyndham Lewis. Writers typically and shamelessly denied that their “creations” had anything to do with the victims even when it was self-evident. Huxley parodied Gertler and Bertrand Russell, among others who frequented Garsington, and vehemently denied his characters were based on them. Turner created characters based on Bloomsbury luminaries including Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf, and used them to pummel Lady Ottoline: One character described her as a woman from whom “normal males have invariably fled before her eagerly offered embraces.” Another wondered if there was a human face “underneath the chalky mask, with its withered, lip-salved gash.”

Other long-forgotten novels of this genre include Diary of a Nobody by George and Weedon Grossmith and The Green Carnation by Robert Hichens. And Ada Leverson, Violet Schiff’s eldest sister, was a notable satirist of a slightly earlier generation. All of her books, however, as well as those by Hichens and the Grossmiths, were written with a gentler touch than those of Lawrence, Huxley, Turner and especially Lewis. Remarkably though, despite the poisonous quality of their satire, even the most vindictive authors were often forgiven, although it sometimes took a while. In her memoir, Lady Ottoline wrote about Lawrence: “After twelve years the wound had healed and I was very glad to hear again from someone who obviously was fond of me, and in one letter at least he has spoken of me in a way that shows that his real feeling for me was good and appreciative, while now and always I feel he was a very lovable man.”

There is something touching about this in its neediness, and forgiveness is said to be a virtue. I would leave it at that except in the same memoir Lady Ottoline said she showed the passages in Women in Love to Huxley, who said he was horrified. Women in Love was published in 1920 and Crome Yellow, which similarly skewered the mistress of Garsington, in 1921. Horror among at least some of the modernists, it turns out, was a relatively short-lived feeling. But according to Miranda Seymour, who wrote an adoring biography of Lady Ottoline, the way her friends characterized her had no malicious intent. It had to do with “a love of language and gossip.” As Seymour put it rather generously, “sincerity was sacrificed to a lively turn of phrase.” There may be something to this, but assuming there is I’m not sure whether we should like Bloomsbury more or less.

In any event, Sydney, a conspicuous victim of this particular species of nastiness, who could be unsparing in his verbal candor, never sacrificed sincerity to a lively turn of phrase in his books. His reaction to Lewis’s searing satire of him and Violet in a novel called The Apes of God, the pu

blication of which put an end to their somewhat tortured relationship, was more sorrow than anger. Violet, who was more philosophical and less easily wounded, kept up a sporadic correspondence with Lewis even after Sydney died.

CHAPTER 1

SYDNEY’S TRAVELS

In the year of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, 1887, a rather effete-looking, pink-cheeked, eighteen-year-old Londoner named Sydney Schiff set sail from England. His destination was an immense cattle ranch in the Canadian west where he was being sent by his father to work and ponder his future. It was a compromise of sorts worked out after Sydney had rejected a position at A. G. Schiff & Co., his family’s merchant banking firm, and refused to attend Oxford on his father’s terms. Alfred Schiff had been willing to send his son to the university, but only as a prelude to working at the firm, and only if he prepared for a learned profession such as the law, which would be useful in banking. It was not the first time Sydney had displeased his father, about his future among other things. And it would not be the last. Alfred, like most Victorian males of his class and generation, believed his son owed him absolute obedience and he found Sydney’s disregard of his wishes deeply disrespectful.

He was not a patient man, so having been turned down twice one has to wonder what possessed him to offer Sydney a way out. Perhaps he believed the experience would be unpleasant enough to make banking look more attractive. But if that’s what he thought, he badly misjudged his son. Another possibility is that he thought exposure to North America’s aggressive commercial culture would be good for Sydney. He might even have offered to arrange a job on the ranch, thinking Sydney would turn it down. After all, why would he expect that someone who was no one’s idea of a rugged outdoorsman—whose tastes ran to books and pictures, and who was brought up with every comfort wealth could buy—would want to leave London, the world’s most vibrant city, for the vacuous grasslands of Alberta? He knew his son loved horses, but that would hardly have been sufficient, all of which raises another obvious question: Why did Sydney go? Perhaps it was the prospect that he would be six thousand miles away from his father. What seems self-evident, though, is that Alfred’s efforts to change Sydney’s mind about joining A. G. Schiff & Co. were doomed from the start. He simply could not grasp that his son equated a career in banking with the loss of his soul.

Sydney and Violet

Sydney and Violet